Showing posts with label Mongolia. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Mongolia. Show all posts

Saturday, June 21, 2014

Today in Mongol Imperial History

On this day in 1307 Kulug Khan was enthroned as Emperor of the Mongols (Emperor Wuzong of the Great Yuan in China). An accomplished warrior, he ruled in the fashion of a traditional Mongol chieftain, making him very popular with the other Mongol princes but less popular with the Han people of China. He supported the major religions and the military, completing the seizure of Sakhalin Island during his reign.

Friday, April 4, 2014

Where Chinese Rule Is Wrong

The title of this may be a bit confusing. As a monarchist, I find everything about the rule of communist China (or “communist” China) wrong but what I am talking about here specifically is the controversy about certain areas that are currently ruled by the People’s Bandit Republic of China which that regime has absolutely no right to. The most prominent of these areas, certainly in the west and which probably has the highest profile worldwide, is Tibet. Why is there a dispute over the Chinese rule of Tibet? Why is this the only dispute most people have heard about? More people know about Tibet mostly because the Tibetan exile community has elements in many countries and because of the inspirational leadership of His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama who so many people around the world have come to respect and admire for his compassion and devotion to peace. The bandit regime in Peking has absolutely no right to Tibet but it also has no right to some other areas most people do not think about such as Manchuria (now called simply the northeast as part of the program, sadly mostly successful by this point, to eradicate Manchuria from existence) and Mongolia. Now, as most probably know, China does not rule Mongolia which is an independent country though teetering between dependence on China and Russia. However, the communists in Peking have claimed it in the past and the Republic of China, on Taiwan, which still maintains a claim to rule the whole of mainland China, also still, technically, include Mongolia in that claim. So, why all the confusion?

Basically, it all goes back to the last time China had a monarchy and the efforts by the republicans and communist bandits to claim the entire legacy of traditional, imperial China as their own. Save, perhaps, for the period when China was part of the Mongol Yuan Empire, the place most in the world think of as China reached its greatest height under the Manchu emperors of the Great Qing Dynasty. The borders that existed at the height of the Great Qing Empire are the borders the communists in Peking would most like to see restored. The problem with that is that those were the borders of the Great Qing Empire and not really the borders of China. Confused yet? It can seem quite complicated so pay close attention and we will try to take this one step at a time. What most of the world calls “China” is, of course, not a Chinese term but is a western term. The Chinese never called their country “China” in all of their multi-thousand year history prior to the revolution. This area was referred to as “the Middle Kingdom” which can itself be a bit confusing since this referred not only to China proper but actually meant the entire world; everything above the underworld and below Heaven -the “Middle Kingdom”. The ruler of China was considered, in traditional Chinese political philosophy, to be the ruler of the entire world it was only that some remote, barbarian peoples on the edges of the earth were too ignorant to understand this. It was a way of thinking which must be kept in mind when considering how China interacted with foreign powers and why the communists today seize on this interaction to justify their claims for more territory.

Traditionally, Chinese rulers would not deal with any outsider unless they presented themselves as a supplicant and recognized or at least pretended to recognize the Chinese Emperor as their superior. This attitude persisted for almost the entirety of Chinese history. For example, when China and Japan first established diplomatic relations things got off to a bad start as the message from the Emperor of Japan to the Emperor of China was addressed as ‘from the land where the sun rises to the land where the sun sets’ referring to Japan being to the east of China. However, the Chinese took this as being extremely rude and offensive as they saw it as implying that the Emperor of Japan was the equal of the Emperor of China. Move forward many, many centuries in time and we can see again the case of the first British diplomatic mission to China which ran into a considerable obstacle over the refusal of the British ambassador to present himself as a subject and kowtow before the Manchu Emperor, getting down on both knees and touching his forehead to the floor. Today, the Chinese Communist kleptocracy claims that any ruler or representative of a ruler who recognized the Chinese Emperor as his superior or overlord in this fashion was effectively making his country a part of China when, as we can see, this would apply to almost every foreign ruler or dignitary any Chinese Emperor ever met because they would not deal with anyone unless they assumed such a posture.

This situation is further complicated by the fact that not all such tributaries were of equal status. The Emperor in China might have more or less influence in one of the other but none were directly under Chinese rule or were considered a part of China. As early as the Tang Dynasty, for example, the kingdoms in what is now Korea were nominal vassals of the Tang Emperor but retained their own rulers. Under the Ming Dynasty, the unified Kingdom of Korea was likewise a vassal of the Ming Emperor or, in terms more familiar to westerners perhaps, a Chinese protectorate. So, when Japan invaded Korea in 1592 the Ming Emperor sent hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops to defend (or in this case re-take) Korea. However, the King of Korea was still the local authority and Korea was never considered a part of China itself. Similarly, there were periods when Chinese Emperors ruled Vietnam but they were invariably driven out. However, every time this occurred, almost immediately, the victorious Vietnamese dynasty would send envoys to Peking to present themselves as the vassals of the Emperor in China and to request his ‘seal of approval’ on their government. The Chinese did not rule Vietnam and, in fact, inside Vietnam the monarch was often referred to as the ‘Emperor’ while he was referred to as ‘King’ when dealing with the ruler of China. It was a way to keep the peace by allowing the Emperor in China to save face, being treated as the superior while in fact the local Vietnamese monarch actually ruled the country. Again, this was rather like a protectorate as when the last Le dynasty emperor was overthrown, he called on China to restore him and this situation endured until the Sino-French War.

Obviously, no one today would consider Korea or Vietnam to be a part of China nor any of the other neighboring countries which paid tribute to the Chinese Emperor. Problems, and confusion, arise partly because of the different understanding of what makes a country. As stated earlier, the Chinese did not view their country as “China” in the same way that foreigners viewed their own countries. When the Chinese referred to their country, when not referring to it as the broader “Middle Kingdom” the Chinese always referred to the dynasty so that the country was whatever territory the Emperor had under his direct control which might have included most, some or even relatively little of what is labeled as China on maps of today. So, rather than saying “China” the Chinese would refer to their country, under the Ming Dynasty for example, as the “Great Ming Empire” (Ta Ming Kuo) and then as the “Great Qing Empire” (Ta Qing Kuo) under the Manchurian dynasty. The Ming Empire, for example, included all of “China” which is to say the historic lands sometimes referred to (somewhat oddly) as “China proper” but did not include Tibet, Mongolia or Manchuria though parts of southern Manchuria and southern Mongolia were under Ming rule for a relatively short time. Today, what the Chinese government likes to claim is that territory which was part of the Great Qing Empire at its height, which included Tibet, Mongolia and Manchuria (obviously, as the Qing Dynasty was the native dynasty of Manchuria) as well as smaller parts of various neighboring powers.

The absurdity of this can, perhaps, best be illustrated by skipping backward, over the Ming Dynasty, to the Yuan Dynasty. As regular readers will know, the Yuan Dynasty was the Mongolian dynasty and refers to that period when China was part of the vast Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan with his grandson Kublai Khan being counted as the first Yuan Emperor as it was he who conquered the remainder of China itself; what had been the southern Song Dynasty. What was directly under the rule of the Yuan Emperors was restricted to basically the east Asian mainland north of Vietnam, extending all the way into Siberia. However, the wider Mongol Empire stretched all the way to well inside Eastern Europe. For China today to claim Tibet or Manchuria as being a part of China because all were part of the Qing Empire would be just as absurd as claiming that Siberia is a part of China because it was part of the Yuan Empire. Any claim to Mongolia is just as silly. No Chinese Emperor, meaning an Emperor of the Han nationality from “China proper” ever ruled all of Mongolia or Manchuria but under the Yuan and Qing Dynasties the Mongol and later Manchu Emperors did rule all of China. To put it another way, Mongolia nor Manchuria were ever a part of China but China was, in a manner of speaking, a part of Mongolia and Manchuria during those eras when the Mongol and Manchu Emperors ruled China.

This is the history: When the Ming Empire was in its final days the Qing Dynasty was already well established as the leaders of the Empire of Manchuria. The Manchu Emperor formed an alliance with the Mongols and was granted sovereignty over them when the son of Ligden Khan (last Mongol Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty that had previously ruled most of Asia) handed the imperial seal over to the Manchu Emperor Hong Taiji, who was himself the son of the first Qing Emperor Nurhaqi. Thus Hong Taiji became Emperor of Manchuria and Great Khan of Mongolia. Meanwhile, to the south, the Ming Empire was coming apart. In 1644 Peking was taken by the rebel army of Li Zicheng with the last Ming Emperor, Chongzhen, committing suicide. Li Zicheng proclaimed himself the master of a new Shun Dynasty but a combined force of Chinese, Manchu and Mongol troops ousted him and he disappeared, making the Manchu Emperor Shunzhi the ruler of China, having dispatched an illegitimate usurper and restoring peace and order to China, which became part of the Great Qing Empire -an empire that already existed in Manchuria and Mongolia. Emperor Shunzhi also received an official visit by His Holiness the “Great Fifth” Dalai Lama. The Qing emperors had been protectors of the Tibetan style of Buddhism since the reign of Nurhaqi and, of course, there were deep ties between Mongolia and Tibet with the Mongols having helped establish the Dalai Lamas in the first place and with the Dalai Lamas holding spiritual authority over Mongolia as well as Tibet.

As we have seen, Mongolia and Manchuria were independent countries which came to share a monarch and then that monarch was also recognized as the ruler of China, holding the Mandate of Heaven. China never conquered or annexed Manchuria and Mongolia, in fact, what happened was closer to the reverse of that. In the same way, it is important to note that when the Great Fifth visiting Peking it was as one sovereign visiting another. His successor, was overthrown and in the ensuing chaos the Qing Emperor Kangxi sent troops to see order restored and the legitimate Dalai Lama secured on his throne. It was at that point and only at that point that the Kingdom of Tibet was declared a protectorate of the Great Qing Empire. That, of course, did not make Tibet a part of China. The Dalai Lama remained the ruler of Tibet with the only change being that two Qing commissioners and a small military force were stationed there and, in the future, Tibet did call on the Qing Empire for assistance in times of crisis. For those who claim that Tibet has “always” been a part of China, one would have to ask why there were no representatives from Peking there in the first place. Why is mention made of the annexation of Tibetan border territories to Chinese provinces if Tibet was entirely part of China already? Obviously, this is nonsense. Tibet was an independent country and it was only when neighboring countries invaded Tibet and Qing troops were sent in to defend the place that Qing Imperial influence was most felt in the aftermath.

Hopefully, this has made clear the absurdity of the Republic of China (and more so the People’s Republic of China) claiming Tibet, Mongolia and Manchuria to have “always” been a part of China. When the revolution occurred, Manchuria naturally had no part in it and Mongolia and Tibet were both quick to make clear to the rest of the world that they were independent, issuing joint declarations to that effect. This was because their association with China was based solely on their relationship with the Qing Emperor and not the country of China itself. Once the Manchu Emperor was deprived of his throne, all deals were off. That independence was temporarily retained for Tibet, remaining independent until communist Chinese troops conquered the country in 1951. Mongolia (or at least Outer Mongolia) remains independent to this day though it was certainly not an easy achievement. Manchuria became, effectively, a warlord “monarchy” ruled by a warlord father and son in succession while they offered nominal allegiance to the Republic of China. All of that changed when the Japanese occupied Manchuria and in 1932 independence was declared for the State of Manchuria, later to be fully restored as the Empire of Manchuria. That, of course, is what should have happened from the beginning and some Chinese officials even admitted as much.

There was no justification for the Han Chinese to think they were somehow entitled to Manchuria just because China and Manchuria had been part of the same empire. As soon as the Qing Emperor was forced to abdicate in Peking, he should have been able to immediately withdraw to the old Qing Imperial Palace in Mukden and continue to rule over Manchuria as his ancestors had done before accepting the allegiance of the Chinese. For China to claim Manchuria as part of their own national territory would be as absurd as the United States, after winning the Revolutionary War, claiming Great Britain and Ireland to be American territory just because both had previously been part of the same empire. That being so, when the polyglot army of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg drove the Chinese out of Mongolia in 1921, he was expelling invaders and restoring the country to its only available legitimate leader. Likewise, when the Japanese restored the last Qing Emperor to the throne of Manchuria they were correcting a gross historical injustice and when the Soviets (in total violation of their pledged word) invaded and destroyed that empire and handed it over to China again, they were essentially giving recovered property back to the thieves. In the same way, if by some chance the Dalai Lama is ever restored to the Potala Palace in Tibet, it will be correcting a horrible injustice. When the republicans, and certainly the communists, took over China, they turned their back on and even attempted to destroy all that had gone before them and the legacy of the emperors in particular. It is the height of hypocrisy to then attempt to claim those borders which only existed because of the emperors as their own inheritance.

|

| Song Empire |

Traditionally, Chinese rulers would not deal with any outsider unless they presented themselves as a supplicant and recognized or at least pretended to recognize the Chinese Emperor as their superior. This attitude persisted for almost the entirety of Chinese history. For example, when China and Japan first established diplomatic relations things got off to a bad start as the message from the Emperor of Japan to the Emperor of China was addressed as ‘from the land where the sun rises to the land where the sun sets’ referring to Japan being to the east of China. However, the Chinese took this as being extremely rude and offensive as they saw it as implying that the Emperor of Japan was the equal of the Emperor of China. Move forward many, many centuries in time and we can see again the case of the first British diplomatic mission to China which ran into a considerable obstacle over the refusal of the British ambassador to present himself as a subject and kowtow before the Manchu Emperor, getting down on both knees and touching his forehead to the floor. Today, the Chinese Communist kleptocracy claims that any ruler or representative of a ruler who recognized the Chinese Emperor as his superior or overlord in this fashion was effectively making his country a part of China when, as we can see, this would apply to almost every foreign ruler or dignitary any Chinese Emperor ever met because they would not deal with anyone unless they assumed such a posture.

|

| Viet envoys to Qing court in China |

Obviously, no one today would consider Korea or Vietnam to be a part of China nor any of the other neighboring countries which paid tribute to the Chinese Emperor. Problems, and confusion, arise partly because of the different understanding of what makes a country. As stated earlier, the Chinese did not view their country as “China” in the same way that foreigners viewed their own countries. When the Chinese referred to their country, when not referring to it as the broader “Middle Kingdom” the Chinese always referred to the dynasty so that the country was whatever territory the Emperor had under his direct control which might have included most, some or even relatively little of what is labeled as China on maps of today. So, rather than saying “China” the Chinese would refer to their country, under the Ming Dynasty for example, as the “Great Ming Empire” (Ta Ming Kuo) and then as the “Great Qing Empire” (Ta Qing Kuo) under the Manchurian dynasty. The Ming Empire, for example, included all of “China” which is to say the historic lands sometimes referred to (somewhat oddly) as “China proper” but did not include Tibet, Mongolia or Manchuria though parts of southern Manchuria and southern Mongolia were under Ming rule for a relatively short time. Today, what the Chinese government likes to claim is that territory which was part of the Great Qing Empire at its height, which included Tibet, Mongolia and Manchuria (obviously, as the Qing Dynasty was the native dynasty of Manchuria) as well as smaller parts of various neighboring powers.

|

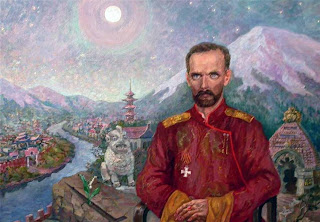

| Emperor Nurhaqi of Manchuria |

This is the history: When the Ming Empire was in its final days the Qing Dynasty was already well established as the leaders of the Empire of Manchuria. The Manchu Emperor formed an alliance with the Mongols and was granted sovereignty over them when the son of Ligden Khan (last Mongol Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty that had previously ruled most of Asia) handed the imperial seal over to the Manchu Emperor Hong Taiji, who was himself the son of the first Qing Emperor Nurhaqi. Thus Hong Taiji became Emperor of Manchuria and Great Khan of Mongolia. Meanwhile, to the south, the Ming Empire was coming apart. In 1644 Peking was taken by the rebel army of Li Zicheng with the last Ming Emperor, Chongzhen, committing suicide. Li Zicheng proclaimed himself the master of a new Shun Dynasty but a combined force of Chinese, Manchu and Mongol troops ousted him and he disappeared, making the Manchu Emperor Shunzhi the ruler of China, having dispatched an illegitimate usurper and restoring peace and order to China, which became part of the Great Qing Empire -an empire that already existed in Manchuria and Mongolia. Emperor Shunzhi also received an official visit by His Holiness the “Great Fifth” Dalai Lama. The Qing emperors had been protectors of the Tibetan style of Buddhism since the reign of Nurhaqi and, of course, there were deep ties between Mongolia and Tibet with the Mongols having helped establish the Dalai Lamas in the first place and with the Dalai Lamas holding spiritual authority over Mongolia as well as Tibet.

|

| Emperor KangXi of the Great Qing |

Hopefully, this has made clear the absurdity of the Republic of China (and more so the People’s Republic of China) claiming Tibet, Mongolia and Manchuria to have “always” been a part of China. When the revolution occurred, Manchuria naturally had no part in it and Mongolia and Tibet were both quick to make clear to the rest of the world that they were independent, issuing joint declarations to that effect. This was because their association with China was based solely on their relationship with the Qing Emperor and not the country of China itself. Once the Manchu Emperor was deprived of his throne, all deals were off. That independence was temporarily retained for Tibet, remaining independent until communist Chinese troops conquered the country in 1951. Mongolia (or at least Outer Mongolia) remains independent to this day though it was certainly not an easy achievement. Manchuria became, effectively, a warlord “monarchy” ruled by a warlord father and son in succession while they offered nominal allegiance to the Republic of China. All of that changed when the Japanese occupied Manchuria and in 1932 independence was declared for the State of Manchuria, later to be fully restored as the Empire of Manchuria. That, of course, is what should have happened from the beginning and some Chinese officials even admitted as much.

|

| Empire of Manchuria |

Friday, March 7, 2014

Story of Monarchy: The Ulus of Jochi

It seems to me that one of the most significant former powers that is all but forgotten today, at least in the western world, is the Ulus of Jochi. Presumably it is more well known in Eastern Europe and Central Asia where it was most dominant but it was a state that everyone should at least be aware of. The Ulus of Jochi (also later known in the west as the Golden Horde) was the dominant power of central Asia for quite some time and it had a significant impact on the course of history in Russia, Europe and the Middle East as well as Central Asia as various people banded together in opposition to the common threat of the dreaded Golden Horde. As the name implies, it has its origins in the career of Jochi Khan, eldest son of the great Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan (Ulus of Jochi simply means the ‘lands/state/realm/territory of Jochi’) who, during the reign of his father, had played a leading part in the Mongol conquest of Siberia, Central Asia and Persia. He was to inherit the westernmost portion of the Mongol Empire when Genghis Khan died but as Jochi predeceased his father the Ulus of Jochi went to his son Batu Khan who is generally regarded as the true founder of this khanate which was part of the wider Mongol Empire.

Ogedei Khan succeeded his father as Great Khan (or Emperor) of the Mongols while the Ulus of Jochi were divided between Batu Khan (who received the Blue Horde) and his brother Orda (who received the White Horde). Before he could concentrate on “nation building”, however, Batu assisted Ogedei Khan in his conquest of the Jin Dynasty of Manchuria while his brother fought Bulgars, Cumens and other peoples in the west. After Manchuria was conquered (it would be left to Kublai Khan to conquer southern China), Batu Khan turned west and took on the formidable task of conquering the Russians. It was a brutal and bitter struggle but, in the end, Batu Khan was successful and the Russian states and all those in the area of modern Russia were devastated from Moscow to the Crimea. He conquered Ruthenia and drove the Cumens into the Kingdom of Hungary but when he demanded that these refugees be expelled, King Bela IV of Hungary not only refused but had the Mongol messengers killed (the Hungarians had a history of dealing with the Cumens, as we have covered previously, having earlier employed the Teutonic Knights against them). Batu Khan was outraged at this defiance and vowed to conquer Hungary and all the land to the Atlantic Ocean. Given that the man had just conquered Russia one can perhaps forgive him for being a bit arrogant.

The Mongols swept westward, conquering Poland, Hungary and Bohemia, besting the forces of the Holy Roman Empire, alarming all of Europe and prompting the Pope to call for a crusade against them. Fortunately for Europe, the Mongols were not to stay long. The death of Odegei Khan prompted a power struggle and Batu Khan, reluctantly, returned home to press his claim to become the next Mongol Emperor. However, that came to nothing with the throne going to Guyuk Khan and so Batu returned to the west to focus on expanding his own central Asian kingdom. He further consolidated his rule and established his capital at Sarai in what is now southern Russia (near what is now Selitrennoye). Batu became so powerful that some believed Guyuk Khan considered him a threat and was preparing to move against him when he died in what is now the western Chinese province of Xinjiang. Batu Khan had reached such a position of influence that he was in large part responsible for placing the next Mongol Emperor, Mongke Khan, on the throne. Batu Khan set up the Princes of Vladimir and St Alexander Nevsky was one of his tributaries. Batu Khan died in 1256 as the master of central Asia and none of his successors would ever be able to outshine him.

Eventually, leadership of the Ulus of Jochi fell to Batu’s younger brother Berke Khan. His reign lacked the smashing conquests of prior years but he still attacked with great ferocity against Lithuania, Poland, the Teutonic Knights and Hungary, even declaring war on the King of France. He is also most remembered for converting to Islam and allying with the Mamluks of Egypt against the Persian-centered Ilkhanate (another successor state of the empire of Genghis Khan). He died fighting his fellow Mongols for power while the overall state of the Golden Horde declined, though he did manage to force the Byzantine Emperor to pay him tribute. He also, just before his death, backed a winner in the person of Kublai Khan who would become Emperor of the Mongols, founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China and rule the largest land empire in history. However, after his death, the Ulus of Jochi was again paralyzed by infighting for power, eventually drawing in Kublai Khan himself. And, of course, in the meantime there were devastating raids into tributaries such as Lithuania and Bulgaria. There was even another invasion of Hungary which proved ruinous but which was a failure. During this time it was the Hungarians who most often proved to be the sentinels of Europe against Mongol invasion (or “Mongol” invasion as the vast majority of the troops were not Mongolians at all). There were also struggles between the Muslim and Buddhist members of the ruling family but eventually it was Islam that would dominate.

In 1313 Uzbeg came to the throne and made Islam the official, mandatory religion of the Ulus of Jochi, banning Buddhism and the traditional shamanism of the Mongols. Still maintaining the alliance with the Mamluks and even marrying into the Egyptian Royal Family, the Jochi were becoming further and further removed, in both blood and custom, from their Mongol roots. Uzbeg held Russia by setting the local princes against each other and kept his state running by periodic raids into Europe as far as Serbia and Greece. He involved himself in power disputes within the Muslim world and met with setbacks at the hands of the Poles and Hungarians before the spread of the Black Death brought ruin and an end to any dream of the Golden Horde expanding into central and western Europe. As the years past and the Golden Horde descended more and more into civil wars territory began to be steadily lost. The Lithuanians began to rebel and push back, the Russians began to rise in rebellion and it was only by an alliance with the emerging Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that the Golden Horde was able to hold Russia and reassert control over it.

Eventually, however, the Golden Horde was brought down by various powers chipping away at the periphery. The Russians began to unify and rise against them, the Moldavians fought back, the Turks were expanding from the south and by that time the last ties with China and the Mongolian homeland had long been cut. A last, desperate invasion of the Kingdom of Poland was mounted in 1491 but it was defeated and very soon what had once been the Golden Horde was reduced to being the Crimean Khanate, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire. The last Khan of the Ulus of Jochi was forced to flee to Lithuania and died in prison. Eventually, the Russians would unite and the last remnant of the Golden Horde would be annexed to the Russian Empire by Empress Catherine the Great.

Although not always given a high profile, the Ulus of Jochi had a profound impact on world history and the development of many countries we know today. It was the western frontier of the great Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan. Russia united and became the strong country we all know, famous for immense endurance, after being ruled for quite a long time by the Tartars. The effect this had on the history of Russia and the Russian national character cannot be dismissed. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed, in part, because of the shared threat they faced from the Golden Horde. The Hungarians proved themselves matchless warriors and gained the support of western Europe for standing on the frontline against Tartar expansion and much of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire came about because of the weakening of the Ulus of Jochi. As a monarchy, it was not terribly stable or effectively managed, but its life, though long past, left a legacy that is still felt even today by the peoples of central Asia and Eastern Europe.

|

| Batu Khan |

The Mongols swept westward, conquering Poland, Hungary and Bohemia, besting the forces of the Holy Roman Empire, alarming all of Europe and prompting the Pope to call for a crusade against them. Fortunately for Europe, the Mongols were not to stay long. The death of Odegei Khan prompted a power struggle and Batu Khan, reluctantly, returned home to press his claim to become the next Mongol Emperor. However, that came to nothing with the throne going to Guyuk Khan and so Batu returned to the west to focus on expanding his own central Asian kingdom. He further consolidated his rule and established his capital at Sarai in what is now southern Russia (near what is now Selitrennoye). Batu became so powerful that some believed Guyuk Khan considered him a threat and was preparing to move against him when he died in what is now the western Chinese province of Xinjiang. Batu Khan had reached such a position of influence that he was in large part responsible for placing the next Mongol Emperor, Mongke Khan, on the throne. Batu Khan set up the Princes of Vladimir and St Alexander Nevsky was one of his tributaries. Batu Khan died in 1256 as the master of central Asia and none of his successors would ever be able to outshine him.

Eventually, leadership of the Ulus of Jochi fell to Batu’s younger brother Berke Khan. His reign lacked the smashing conquests of prior years but he still attacked with great ferocity against Lithuania, Poland, the Teutonic Knights and Hungary, even declaring war on the King of France. He is also most remembered for converting to Islam and allying with the Mamluks of Egypt against the Persian-centered Ilkhanate (another successor state of the empire of Genghis Khan). He died fighting his fellow Mongols for power while the overall state of the Golden Horde declined, though he did manage to force the Byzantine Emperor to pay him tribute. He also, just before his death, backed a winner in the person of Kublai Khan who would become Emperor of the Mongols, founder of the Yuan Dynasty in China and rule the largest land empire in history. However, after his death, the Ulus of Jochi was again paralyzed by infighting for power, eventually drawing in Kublai Khan himself. And, of course, in the meantime there were devastating raids into tributaries such as Lithuania and Bulgaria. There was even another invasion of Hungary which proved ruinous but which was a failure. During this time it was the Hungarians who most often proved to be the sentinels of Europe against Mongol invasion (or “Mongol” invasion as the vast majority of the troops were not Mongolians at all). There were also struggles between the Muslim and Buddhist members of the ruling family but eventually it was Islam that would dominate.

In 1313 Uzbeg came to the throne and made Islam the official, mandatory religion of the Ulus of Jochi, banning Buddhism and the traditional shamanism of the Mongols. Still maintaining the alliance with the Mamluks and even marrying into the Egyptian Royal Family, the Jochi were becoming further and further removed, in both blood and custom, from their Mongol roots. Uzbeg held Russia by setting the local princes against each other and kept his state running by periodic raids into Europe as far as Serbia and Greece. He involved himself in power disputes within the Muslim world and met with setbacks at the hands of the Poles and Hungarians before the spread of the Black Death brought ruin and an end to any dream of the Golden Horde expanding into central and western Europe. As the years past and the Golden Horde descended more and more into civil wars territory began to be steadily lost. The Lithuanians began to rebel and push back, the Russians began to rise in rebellion and it was only by an alliance with the emerging Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that the Golden Horde was able to hold Russia and reassert control over it.

Eventually, however, the Golden Horde was brought down by various powers chipping away at the periphery. The Russians began to unify and rise against them, the Moldavians fought back, the Turks were expanding from the south and by that time the last ties with China and the Mongolian homeland had long been cut. A last, desperate invasion of the Kingdom of Poland was mounted in 1491 but it was defeated and very soon what had once been the Golden Horde was reduced to being the Crimean Khanate, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire. The last Khan of the Ulus of Jochi was forced to flee to Lithuania and died in prison. Eventually, the Russians would unite and the last remnant of the Golden Horde would be annexed to the Russian Empire by Empress Catherine the Great.

Although not always given a high profile, the Ulus of Jochi had a profound impact on world history and the development of many countries we know today. It was the western frontier of the great Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan. Russia united and became the strong country we all know, famous for immense endurance, after being ruled for quite a long time by the Tartars. The effect this had on the history of Russia and the Russian national character cannot be dismissed. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed, in part, because of the shared threat they faced from the Golden Horde. The Hungarians proved themselves matchless warriors and gained the support of western Europe for standing on the frontline against Tartar expansion and much of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire came about because of the weakening of the Ulus of Jochi. As a monarchy, it was not terribly stable or effectively managed, but its life, though long past, left a legacy that is still felt even today by the peoples of central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Mongolia, Monarchy and Hope

Recently, NHK reported that Mongolia (independent Outer Mongolia) was seeking closer ties with the State of Japan as an alternative to the ever-encroaching pressure from Russia to their north and China to their south. This is not an altogether new position for Mongolia to be in and it is not the first time that Mongols have looked for support from Japan in the face of domination from their more immediate neighbors. In the past, monarchy played a key role in this drama and it is something worth considering as few people tend to be very familiar with the monarchial history of Mongolia, at least following the fall of the massive Mongol Empire that once dominated most of the known world. Many people seem to be under the mistaken belief that Mongolia was, at some point, conquered by Imperial China. Such is not the case. Mongolia was never a part of Imperial China but China could be said to have been part of Mongolia for a time. As most know, Genghis Khan conquered most of northern China and it was left to his grandson, Kublai Khan, to conquer the rest of China and establish the Great Yuan Empire, the Yuan Dynasty being one of the major imperial dynasties of Chinese history. Eventually, the Mongols were displaced and China came under the rule of the Ming Dynasty as the Great Ming Empire of which Mongolia was never a part.

Just because the Mongols were evicted from ruling China does not mean it all came to an end. They retreated to their Mongolian homeland and continued there as the “Northern Yuan Dynasty” until the reign of Ligden Khan. After his death many Mongols, and they were fractured at the time, allied with the rising power of the Manchus and the son of Ligden Khan handed over the dynastic seal to Hong Taiji, son of Nurhaci who was the founder of the Manchu Qing Dynasty. The Manchus and the Mongols were then allies and the Mongols certainly saw themselves as partners with the Manchus in taking control of China and establishing the Great Qing Empire. Because of this, the monarchial tradition in Mongolia continued in the person of the Manchu Emperor who also held the title ‘Great Khan of the Mongols’. This continued up until the duplicitous overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in 1911/1912 with the abdication of the famous ‘last emperor’. Already, by that time, Mongolia was feeling pressure from the Russian Empire. In the agreements drawn up among the European powers, Mongolia and Manchuria were both considered to be part of the Russian sphere of influence. However, when the Qing Dynasty lost power, it happened with the Mongols (and the Manchus for that matter) having no say in the decision and they were not prepared to just accept being a part of the Republic of China when they had never been ruled by China.

It was at this time that the last monarch to hold power in Outer Mongolia came to prominence. In the absence of their former monarch, the Qing Emperor, the Mongols turned for leadership to their highest religious official, the Bogd Gegeen or “Holy Shining One” and invested him with secular power as the Bogd Khan of Mongolia. Long-time readers will remember the fate that befell him. He was first removed from power and placed under house arrest by a warlord of the Republic of China only to be liberated and restored in 1921 by the multi-national White Russian-led army of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg. When he was defeated and captured the Bogd Khan spent the rest of his life under house arrest as Outer Mongolia became the first satellite state of the Soviet Union, ruled with the most extreme brutality by a succession of Soviet stooges, the most infamous being the Stalin-worshipping Choibalsan. All the while, the Republic of China still claimed jurisdiction over all of Mongolia just as they did over all lands formerly a part of the Great Qing Empire even though these had never been part of China. So, Outer Mongolia was effectively being ruled by Soviet Russia and Inner Mongolia was being ruled (somewhat intermittently) by the Republic of China which also claimed Outer Mongolia as their own as well but were still fighting among themselves for control of what territory they actually occupied.

An obvious place to look to for help in this situation was the Empire of Japan. There had, in fact, been some elements in Japan working for some time on forging a pan-monarchist coalition across northeast Asia of Japanese, Manchus and Mongols. It was to further cement such an alliance that the tough, colorful Japanese-raised Manchu princess, Kawashima Yoshiko, was (briefly) married into one of the leading Mongol noble families. However, whereas Outer Mongolia had to be taken off the priority list after the ineffective border clashes with the Soviet Red Army and the subsequent Soviet-Japanese Non-Aggression Pact, Inner Mongolia remained a region of potential. In this area, the man looked to for leadership was Prince Demchugdongrub or Prince De Wang. He had been loyal to the Qing Emperor during his time in the Forbidden City and after his expulsion and exile to Tientsin. He also visited the Emperor after he was restored to the throne in Manchuria. The Japanese Kwantung Army, operating in Manchuria, supported Prince De Wang in establishing an autonomous government and while he controlled relatively little territory and his state consisted mostly of an army and a monarchy, he was a pan-Mongol visionary and his ultimate goal was no secret to anyone. That was to reunite all the Mongol peoples into a restored Mongol Empire or, perhaps, even another partnership with the restored Manchu Empire.

As Mengjiang (as it was called -the territory of the Mongols) did not survive the Japanese defeat in 1945 and was conquered by communist forces along with Manchuria, we will never know how it would have developed. Prince De Wang was certainly no puppet, despite what his detractors may say. The first Japanese advances made toward him were rejected and his first official alliance was with the restored Emperor of Manchuria (who may have been his cousin but I am not sure about that) who also bestowed on him a special title. When the Prince did come to an agreement with the Japanese Kwantung Army he remained very alert to any hint of a move that would infringe on his authority. Officially, his regime was autonomous, which it was, but also was seen as something temporary. Even the name, Mengjiang, suggested to all who saw it that the intention was to recover all the lands inhabited by the Mongol people. He always dealt with the Emperor of Manchuria as he would have (and did) in the pre-revolutionary days of the Qing Empire. However, after 1940, Inner Mongolia was listed as an autonomous region of the Reorganized National Government of China led by President Wang Jingwei. However, it was truly autonomous and no activities by the Kuomintang party were permitted there nor were any Han Chinese allowed to settle in Mengjiang.

It seems unlikely then that, even if the war had ended differently, Mengjiang would have remained a part of the Republic of China. The goal of Prince De Wang was always to revive the Mongol nation, reuniting Inner and Outer Mongolia, and most assume that this would have meant that Prince De Wang would have been the monarch of this new restored Mongolia. There was certainly a Royal Family on hand ready to take up the responsibility. However, given his own character and personal history, it is also possible that Mengjiang, somewhat enlarged, would have become a partner with Manchuria again under the reign of Emperor Kang Te (PuYi). It is also encouraging that, unlike the Manchu Emperor, after the war Prince De Wang remained fairly popular amongst the Mongol people despite the best efforts of the communist regimes in both China and Mongolia. He spent about 13 years in a Chinese prison of course as a “traitor” and “collaborator” but his own people still, to a large extent, viewed him as a visionary national leader who wanted to restore Mongol glory and make them a proud and united nation once again. That is something to be thankful for as we move forward.

The unfortunate thing is that Inner Mongolia today is mostly a lost cause. Mongol traditions are slowly going away and the Mongols themselves are being drowned out in a flood of Han Chinese settlers (particularly after the coal boom and other related mineral exploitation in the region). Today Mongols make up only 20% of the population of the “Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region” of the People’s Bandit Republic of China. The Chinese Communist Party is not about to change its ways and no other country or countries will do anything about it because China has the bomb -and if you have the bomb, no one can touch you (which is why so many of the worst regimes want it so badly). Outer, independent, Mongolia, while not encouraging, at least has room for hope. In the absence of a secular monarch, they had the Bogd Khan who ruled until the country became a Soviet client state. In 1926 the communist regime ruled that there would be no further reincarnations but, apparently, the spirit world paid them no heed and after the Soviet collapse it was announced that there had been a reincarnation who was enthroned in 1999 in Mongolia as the spiritual leader of Mongolian Buddhists by the Dalai Lama. That incarnation has since past away and, I presume, the search is continuing for his successor.

If there is to be a royal restoration in Mongolia it seems most likely that the spiritual variety will be the most likely avenue. Of course, the Chinese bandit government has expressed their great displeasure at every kindness or courtesy shown to the Bogd Gegeen or the Dalai Lama in Mongolia and the Mongolian government still tends to be dominated by communists with a cosmetic make-over. However, a restored Bogd Khan would seem to be the least threatening to those in political power and the most likely, at this point, to be able to unite the Mongol people. In the past, some high ranking officials expressed that they were at least open to the idea of having another Bogd Khan as a ceremonial head of state. Unless a more dynamic secular figure comes along who could do better, I would hope that other countries, such as Japan if Mongolia is looking to the Japanese to offset the influence of the Russians and Chinese, would support and encourage the next Bogd Gegeen when his new incarnation is found and made public. I say “hope” because, unfortunately, too many in Japan these days take the monarchy for granted and tend to view things in purely economic or racial terms rather than in terms of politics. The past support for Prince De Wang should serve as an example. Just as in the past, Mongolia is becoming unhappy with their level of dependence on Russia or China and just as in the past, a revival of a traditional Mongol monarchy should be the solution that Japan (and hopefully other countries) unite in support of.

|

| Ligden Khan |

It was at this time that the last monarch to hold power in Outer Mongolia came to prominence. In the absence of their former monarch, the Qing Emperor, the Mongols turned for leadership to their highest religious official, the Bogd Gegeen or “Holy Shining One” and invested him with secular power as the Bogd Khan of Mongolia. Long-time readers will remember the fate that befell him. He was first removed from power and placed under house arrest by a warlord of the Republic of China only to be liberated and restored in 1921 by the multi-national White Russian-led army of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg. When he was defeated and captured the Bogd Khan spent the rest of his life under house arrest as Outer Mongolia became the first satellite state of the Soviet Union, ruled with the most extreme brutality by a succession of Soviet stooges, the most infamous being the Stalin-worshipping Choibalsan. All the while, the Republic of China still claimed jurisdiction over all of Mongolia just as they did over all lands formerly a part of the Great Qing Empire even though these had never been part of China. So, Outer Mongolia was effectively being ruled by Soviet Russia and Inner Mongolia was being ruled (somewhat intermittently) by the Republic of China which also claimed Outer Mongolia as their own as well but were still fighting among themselves for control of what territory they actually occupied.

|

| Prince De Wang |

As Mengjiang (as it was called -the territory of the Mongols) did not survive the Japanese defeat in 1945 and was conquered by communist forces along with Manchuria, we will never know how it would have developed. Prince De Wang was certainly no puppet, despite what his detractors may say. The first Japanese advances made toward him were rejected and his first official alliance was with the restored Emperor of Manchuria (who may have been his cousin but I am not sure about that) who also bestowed on him a special title. When the Prince did come to an agreement with the Japanese Kwantung Army he remained very alert to any hint of a move that would infringe on his authority. Officially, his regime was autonomous, which it was, but also was seen as something temporary. Even the name, Mengjiang, suggested to all who saw it that the intention was to recover all the lands inhabited by the Mongol people. He always dealt with the Emperor of Manchuria as he would have (and did) in the pre-revolutionary days of the Qing Empire. However, after 1940, Inner Mongolia was listed as an autonomous region of the Reorganized National Government of China led by President Wang Jingwei. However, it was truly autonomous and no activities by the Kuomintang party were permitted there nor were any Han Chinese allowed to settle in Mengjiang.

It seems unlikely then that, even if the war had ended differently, Mengjiang would have remained a part of the Republic of China. The goal of Prince De Wang was always to revive the Mongol nation, reuniting Inner and Outer Mongolia, and most assume that this would have meant that Prince De Wang would have been the monarch of this new restored Mongolia. There was certainly a Royal Family on hand ready to take up the responsibility. However, given his own character and personal history, it is also possible that Mengjiang, somewhat enlarged, would have become a partner with Manchuria again under the reign of Emperor Kang Te (PuYi). It is also encouraging that, unlike the Manchu Emperor, after the war Prince De Wang remained fairly popular amongst the Mongol people despite the best efforts of the communist regimes in both China and Mongolia. He spent about 13 years in a Chinese prison of course as a “traitor” and “collaborator” but his own people still, to a large extent, viewed him as a visionary national leader who wanted to restore Mongol glory and make them a proud and united nation once again. That is something to be thankful for as we move forward.

The unfortunate thing is that Inner Mongolia today is mostly a lost cause. Mongol traditions are slowly going away and the Mongols themselves are being drowned out in a flood of Han Chinese settlers (particularly after the coal boom and other related mineral exploitation in the region). Today Mongols make up only 20% of the population of the “Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region” of the People’s Bandit Republic of China. The Chinese Communist Party is not about to change its ways and no other country or countries will do anything about it because China has the bomb -and if you have the bomb, no one can touch you (which is why so many of the worst regimes want it so badly). Outer, independent, Mongolia, while not encouraging, at least has room for hope. In the absence of a secular monarch, they had the Bogd Khan who ruled until the country became a Soviet client state. In 1926 the communist regime ruled that there would be no further reincarnations but, apparently, the spirit world paid them no heed and after the Soviet collapse it was announced that there had been a reincarnation who was enthroned in 1999 in Mongolia as the spiritual leader of Mongolian Buddhists by the Dalai Lama. That incarnation has since past away and, I presume, the search is continuing for his successor.

|

| The (now) late Bogd Gegeen |

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Monarch Profile: Yesun Temur Khan of Mongolia

The great Mongol emperors who ruled after Kublai Khan are often divided by historians into two groups; those who governed more in keeping with Chinese traditions and those who governed as more traditional Mongol conquerors. As all were Mongols, that influence was a constant but among them all, Yesun Temur Khan is usually regard as the farthest removed from any sort of Chinese influence at all. He was born in Outer Mongolia in 1293, the son of Kammala, the firstborn son of Zhen Jin who was a son of the great Kublai Khan. Kammala was granted the prestigious title of “Jinong” with control over the Gobi Desert and the final resting place of Genghis Khan. For a time, it was thought he might be a contender for the throne of the Mongol Empire but was passed over. Nonetheless, he had a prestigious position and upon his death in 1302 his son Yesun Temur succeeded him as Jinong. Throughout the reigns of Kulug Khan, Ayurbarwada Khan and Gegeen Khan, Yesun Temur built up a powerful position for himself, became quite successful and with his powerful army was acknowledged by other Mongol princes as their representative on the steppes of the north, particularly those who held to the traditional Mongol ways.

His great chance came in 1323 when Shidebala Khan was assassinated by a group of Mongol princes whose tribute he had cut in what was a more Sino-style Confucian reign. Empress Dowager Targi had placed him on the throne (though she later came to regret it) because of his connections with the Khunggirad clan and Yesun Temur was welcomed to take the throne because his mother likewise belonged to the same clan and because he could be counted on to rule in a more traditionally Mongolian fashion, essentially jumping over the two previous reigns to that of Khaishan Khan. Some historians have since speculated that Yesun Temur was himself one of the conspirators in the assassination of Shidebala Khan, yet other evidence suggests that he had tried to warn the Emperor of the plot against him but was too late. In any event, he was looked to for leadership and on October 4, 1323 on the banks of the Kherlen River in Mongolia he was handed the badges of office, the imperial seal and thus became Yesun Temur Khan, tenth Great Khan of the Mongols and Emperor Taiding of the Great Yuan (as he was known in China). Two of those who had instigated the downfall of Shidebala Khan were accorded high rank immediately with the Grand Censor Tegshi becoming effectively the Minister of War and Esen Temur appointed Grand Councilor.

No doubt they felt highly pleased with themselves but that didn’t last long. Once Yesun Temur Khan was told what these men had done and that by appointing them to high office he would appear to have been complicit in their crimes, Yesun Temur immediately had them dismissed and executed for treason. With that action, those loyal to Shidebala recognized Yesun Temur as a fair leader they could trust and called on him, likewise, to take the throne and to punish those who had murdered his predecessor. This, Yesun Temur did, sending troops to Dadu and Shangdu where the rebellious officers were executed and the princes who had supported the coup were all sent into exile. Regardless of the justice of this, Yesun Temur equally had in mind that if he left these men alive they would see him as their own creature and attempt to control him and would likely murder him as well if he failed to please them. Traitors can never be trusted. The Chinese tried to persuade him to go even farther and massacre anyone connected with those who had brought down the last Great Khan but Yesun Temur refused to do this, regarding the guilty as sufficiently punished, granting an amnesty to the rest and even returning the property of the guilty men to their families.

Still, if the plotters had wanted a “more Mongolian” Mongol Emperor, that is certainly what they achieved in Yesun Temur Khan. He reigned in the traditional style of a Mongol chieftain from the steppes. In the official history of the Yuan Dynasty he is quoted as saying, “The Empire is a family of which the Emperor is the father” and that is how he tended to rule. Chinese officials were dismissed and he appointed new ministers from Mongolia, from the ranks of those he trusted and who had proven themselves loyal to him. He also reverted to the traditional Mongol practice of religious freedom and impartiality. Where Shidebala Khan had been influenced by the Buddhist Lamas to restrict Islam, Yesun Temur Khan stopped all persecutions and extended religious benefits (such as exemption from conscript labor) to Muslims and Christians. This did not mean these were rewarded and others were punished though as he also continued to support Confucian and Buddhist temples and, like most, still showed favor to the Lama-Buddhist community.

In his rule of the Mongol Empire, he favored those who he knew best, the other princes and nobles of the Mongolian steppes though, unlike some others, he preferred to live more simply and objected to the wasteful spending he witnessed at the imperial court. Peking (as it would later be known) was still a cosmopolitan place, despite the change in leadership styles and it is believed that Yesun Temur was the Great Khan met by the Catholic friar Blessed Odoric of Pordenone during his extensive travels in the Far East. During his reign, one of the important acts of Yesun Temur was the division of the Mongol Empire into eighteen departments whose oversight was placed in the hands of an advisory council called the “Lords of the Provinces”. However, Yesun Temur did not have a great interest in day-to-day administration and like most Mongol princes, tended to dislike bureaucrats. The “Exalted and Decisive Emperor” lived only to the age of 34. He died quite suddenly and unexpectedly on August 15, 1328 in Shangdu (Xanadu). He was succeeded by his son Tugh Temur but as he was overthrown barely a month later he is seldom listed amongst the Mongol emperors.

His great chance came in 1323 when Shidebala Khan was assassinated by a group of Mongol princes whose tribute he had cut in what was a more Sino-style Confucian reign. Empress Dowager Targi had placed him on the throne (though she later came to regret it) because of his connections with the Khunggirad clan and Yesun Temur was welcomed to take the throne because his mother likewise belonged to the same clan and because he could be counted on to rule in a more traditionally Mongolian fashion, essentially jumping over the two previous reigns to that of Khaishan Khan. Some historians have since speculated that Yesun Temur was himself one of the conspirators in the assassination of Shidebala Khan, yet other evidence suggests that he had tried to warn the Emperor of the plot against him but was too late. In any event, he was looked to for leadership and on October 4, 1323 on the banks of the Kherlen River in Mongolia he was handed the badges of office, the imperial seal and thus became Yesun Temur Khan, tenth Great Khan of the Mongols and Emperor Taiding of the Great Yuan (as he was known in China). Two of those who had instigated the downfall of Shidebala Khan were accorded high rank immediately with the Grand Censor Tegshi becoming effectively the Minister of War and Esen Temur appointed Grand Councilor.

No doubt they felt highly pleased with themselves but that didn’t last long. Once Yesun Temur Khan was told what these men had done and that by appointing them to high office he would appear to have been complicit in their crimes, Yesun Temur immediately had them dismissed and executed for treason. With that action, those loyal to Shidebala recognized Yesun Temur as a fair leader they could trust and called on him, likewise, to take the throne and to punish those who had murdered his predecessor. This, Yesun Temur did, sending troops to Dadu and Shangdu where the rebellious officers were executed and the princes who had supported the coup were all sent into exile. Regardless of the justice of this, Yesun Temur equally had in mind that if he left these men alive they would see him as their own creature and attempt to control him and would likely murder him as well if he failed to please them. Traitors can never be trusted. The Chinese tried to persuade him to go even farther and massacre anyone connected with those who had brought down the last Great Khan but Yesun Temur refused to do this, regarding the guilty as sufficiently punished, granting an amnesty to the rest and even returning the property of the guilty men to their families.

Still, if the plotters had wanted a “more Mongolian” Mongol Emperor, that is certainly what they achieved in Yesun Temur Khan. He reigned in the traditional style of a Mongol chieftain from the steppes. In the official history of the Yuan Dynasty he is quoted as saying, “The Empire is a family of which the Emperor is the father” and that is how he tended to rule. Chinese officials were dismissed and he appointed new ministers from Mongolia, from the ranks of those he trusted and who had proven themselves loyal to him. He also reverted to the traditional Mongol practice of religious freedom and impartiality. Where Shidebala Khan had been influenced by the Buddhist Lamas to restrict Islam, Yesun Temur Khan stopped all persecutions and extended religious benefits (such as exemption from conscript labor) to Muslims and Christians. This did not mean these were rewarded and others were punished though as he also continued to support Confucian and Buddhist temples and, like most, still showed favor to the Lama-Buddhist community.

In his rule of the Mongol Empire, he favored those who he knew best, the other princes and nobles of the Mongolian steppes though, unlike some others, he preferred to live more simply and objected to the wasteful spending he witnessed at the imperial court. Peking (as it would later be known) was still a cosmopolitan place, despite the change in leadership styles and it is believed that Yesun Temur was the Great Khan met by the Catholic friar Blessed Odoric of Pordenone during his extensive travels in the Far East. During his reign, one of the important acts of Yesun Temur was the division of the Mongol Empire into eighteen departments whose oversight was placed in the hands of an advisory council called the “Lords of the Provinces”. However, Yesun Temur did not have a great interest in day-to-day administration and like most Mongol princes, tended to dislike bureaucrats. The “Exalted and Decisive Emperor” lived only to the age of 34. He died quite suddenly and unexpectedly on August 15, 1328 in Shangdu (Xanadu). He was succeeded by his son Tugh Temur but as he was overthrown barely a month later he is seldom listed amongst the Mongol emperors.

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

Sunday, April 15, 2012

Monday, March 26, 2012

Consort Profile: Empress Xiaozheyi of China

It seems that in Imperial China, many of the consorts we most remember are those who met a tragic or mysterious end. This was certainly the case with Empress Xiaozheyi (Xiao Che), consort of the Emperor Tongzhi, who remains the subject of one of the great unsolved mysteries of the Great Qing Dynasty. She was born on July 25, 1854 into the Alute clan of the Mongol Plain Blue Banner. Because of her background many works refer to her as Empress Alute. Her father, Chong Ji, was a highly respected mandarin, a professor at the Hanlin Academy and the Secretary of the Bureau of Revenue, probably the most esteemed and accomplished Mongol scholar of his time. Her mother was the daughter of a high-ranking Manchu prince, so she was well placed in the upper echelons of Qing society from the very beginning. Alute was noted for her exceptional intelligence, which is not surprising given the scholarly achievements of her father and he kept his daughter close to him when he was at court, personally seeing to her education. Because of this she had a far more developed intellect than was normally expected for a princess but her proximity to the halls of power also caused her to be noticed by the Empress Dowager Cixi as well as her son Emperor Tongzhi who was immediately taken with her.

Tongzhi had reigned as the “Son of Heaven” since he was five years old, coming to the Dragon Throne in 1861 but it was his mother who was the real power. When the time came for a bride to be chosen for the Emperor it was Tongzhi himself who insisted on the knock-out book-worm Alute as an ideal bride for himself and certainly few would have disputed the wisdom of such a choice. Alute was equally famous for her great intelligence, her great virtue and character as well as her great beauty. One would have been hard pressed to imagine someone better suited to be an empress. Empress Dowager Cixi, on the other hand, was not so impressed but, nonetheless, on September 15, 1872 Alute formally became Empress consort to Emperor Tongzhi while the other candidates, favored by the Empress Dowager, were given the consolation prize of becoming concubines. However, their lives were to be rather boring as Emperor Tongzhi favored Alute more than any other and spent almost every night with her, hardly, if ever, calling for any of his other concubines. Even as a youth, Tongzhi had a reputation for, shall we say, a great deal of diverse romantic experience, but all that seemed to change with his marriage to Alute and while his mother might have been pleased with that, she was not at all pleased that he was spending all his time with his wife to the neglect of the consorts she favored and he was soon taking some interest in actually ruling China. She didn’t like that either and was inclined to put the blame on his new wife.

The Empress Dowager took Empress Alute aside and explained to her that she should not keep her husband all to herself, that whether she recognized it or not she was causing harm but making Tongzhi neglect his other consorts. Alute, of course, was intentionally doing nothing of the sort. She came when the Emperor called and could hardly be held to blame for him not calling others. Appealing to her famous intellect, the Empress Dowager also suggested that Alute and the Emperor devote more of their time to study rather than romance and, of course, to do so separately so that the lovely girl would not distract her lustful husband. Tongzhi, however, wanted nothing to do with anything that kept him apart from Alute for long and she was just as devoted to him, no matter how odd a couple they seemed, the playboy and the nerdy girl, so finally the Empress-Dowager acted on her own considerable authority to have the two kept apart. This was unfortunate as the Emperor, deprived of the companionship of his wife, soon returned to his former licentious ways with the help of his eunuchs who were eager to indulge his every whim. Soon he was being smuggled out of the palace to the various dens of iniquity around Peking where, by most accounts, his lifestyle led him to contract syphilis.

Emperor Tongzhi became increasingly bad tempered as well as increasingly ill because of this state of affairs and Empress Alute became more and more depressed, however, she had enough intellect and sufficient will to hold out hope. When she was allowed to tend to her husband her thoughts were always on his recovery and what changes they would make when that time came. Eunuchs reported to the Empress Dowager that Alute often complained about her dominance of the government and interference in her life and that of her husband. Needless to say, the Empress Dowager did not take kindly to this and began to view her daughter-in-law not only as a hindrance to her but as an actual threat and perhaps her son as well, though that was of course blamed on the influence of his over-intelligent wife. Reportedly, the Empress Dowager listened in on one such conversation and then burst into the room in a rage, attacked Alute and ordered her to stay away from the Emperor, having her eunuchs take the Empress away and keep her more or less under guard.

Empress Alute was despondent and her despair increased when Emperor Tongzhi died on January 12, 1875. The Empress was reportedly pregnant at the time but as the Emperor had no children it was up to the Empress Dowager to decide the succession and she chose her nephew who became the tragic Emperor GuangXu. Empress Alute was refused the title of Dowager Empress or any of the other traditional privileges of the widow of an Emperor of China. She was kept virtually in a state of arrest and her food allowance was drastically cut, weakening her considerably. Here is where the real mystery begins. The generally accepted story is that she wrote to her father asking for help and that he replied telling her, in so many words, that suicide was the only honorable way out. Not long after, on March 27, Alute was dead, the official verdict from the imperial court being that she succumbed to an illness.

Immediately though many believed she had killed herself in despair over her situation and on the advise of her father. However, there are some problems with this story which cause many to doubt it. For one thing, it would have been no small trick for her to get a message out of the Forbidden City to her father without the knowledge of the Empress-Dowager, to say nothing of him being able to freely reply back. If this did happen, was his response authentic? Given how he had always been so close to his daughter it seems at least slightly questionable that he would advise her to take her own life. Likewise, the sudden onset of so terrible an illness has caused some to believe that she had been poisoned, probably on orders from the Empress Dowager who was certainly not above such tactics. The angry reaction of the Empress Dowager to any kind words about Alute would seem to support this theory. Additionally, even if it was simply a death from natural causes, the fact that her food allowance had been cut so dramatically would have weakened her health and made her more susceptible to illness, so the Empress Dowager would still not be totally free from blame in that case. So, what was it? Did she die of natural causes as the court claimed, did she commit suicide or was she poisoned by a spiteful mother-in-law. We may never know for sure and so the true fate of the tragic Empress Alute will likely remain one more of the many secrets held within the massive walls of the Great Within.

Tongzhi had reigned as the “Son of Heaven” since he was five years old, coming to the Dragon Throne in 1861 but it was his mother who was the real power. When the time came for a bride to be chosen for the Emperor it was Tongzhi himself who insisted on the knock-out book-worm Alute as an ideal bride for himself and certainly few would have disputed the wisdom of such a choice. Alute was equally famous for her great intelligence, her great virtue and character as well as her great beauty. One would have been hard pressed to imagine someone better suited to be an empress. Empress Dowager Cixi, on the other hand, was not so impressed but, nonetheless, on September 15, 1872 Alute formally became Empress consort to Emperor Tongzhi while the other candidates, favored by the Empress Dowager, were given the consolation prize of becoming concubines. However, their lives were to be rather boring as Emperor Tongzhi favored Alute more than any other and spent almost every night with her, hardly, if ever, calling for any of his other concubines. Even as a youth, Tongzhi had a reputation for, shall we say, a great deal of diverse romantic experience, but all that seemed to change with his marriage to Alute and while his mother might have been pleased with that, she was not at all pleased that he was spending all his time with his wife to the neglect of the consorts she favored and he was soon taking some interest in actually ruling China. She didn’t like that either and was inclined to put the blame on his new wife.

|

| Emperor Tongzhi |

Emperor Tongzhi became increasingly bad tempered as well as increasingly ill because of this state of affairs and Empress Alute became more and more depressed, however, she had enough intellect and sufficient will to hold out hope. When she was allowed to tend to her husband her thoughts were always on his recovery and what changes they would make when that time came. Eunuchs reported to the Empress Dowager that Alute often complained about her dominance of the government and interference in her life and that of her husband. Needless to say, the Empress Dowager did not take kindly to this and began to view her daughter-in-law not only as a hindrance to her but as an actual threat and perhaps her son as well, though that was of course blamed on the influence of his over-intelligent wife. Reportedly, the Empress Dowager listened in on one such conversation and then burst into the room in a rage, attacked Alute and ordered her to stay away from the Emperor, having her eunuchs take the Empress away and keep her more or less under guard.

|

| Empress Dowager Cixi |

Immediately though many believed she had killed herself in despair over her situation and on the advise of her father. However, there are some problems with this story which cause many to doubt it. For one thing, it would have been no small trick for her to get a message out of the Forbidden City to her father without the knowledge of the Empress-Dowager, to say nothing of him being able to freely reply back. If this did happen, was his response authentic? Given how he had always been so close to his daughter it seems at least slightly questionable that he would advise her to take her own life. Likewise, the sudden onset of so terrible an illness has caused some to believe that she had been poisoned, probably on orders from the Empress Dowager who was certainly not above such tactics. The angry reaction of the Empress Dowager to any kind words about Alute would seem to support this theory. Additionally, even if it was simply a death from natural causes, the fact that her food allowance had been cut so dramatically would have weakened her health and made her more susceptible to illness, so the Empress Dowager would still not be totally free from blame in that case. So, what was it? Did she die of natural causes as the court claimed, did she commit suicide or was she poisoned by a spiteful mother-in-law. We may never know for sure and so the true fate of the tragic Empress Alute will likely remain one more of the many secrets held within the massive walls of the Great Within.

Sunday, March 4, 2012

The IX Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa Passes Away

It was just brought to my attention that on Thursday, March 1, His Eminence the Ninth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa Dorjee Chang Jampel Namdrol Choekyi Gyaltsen, spiritual head of the Janang tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and the spiritual Buddhist head of Mongolia, spiritual successor of the last Holy Khan of the Mongols, passed away at the age of 80 at 5.58am (IST) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. A special prayer service was held by HH the XIV Dalai Lama in his memory. You can read his obituary here. Although his passing is a sad occasion, it is perhaps fortunate that it came at such a time when the Dalai Lama will be able to preside over the search for his reincarnation. Had this sad event happened later, I could imagine a great deal of division and discord over the selection of his successor.

Readers interested in learning more about this remarkable man and his situation can look back at posts on How the Revolution Came to Mongolia and The IX Bogd Gegeen and Monarchism in Mongolia. It is unfortunate that a full restoration was not possible in his lifetime, though some progress was made with some political and military officials favoring at least some sort of official, ceremonial role for the "Holy Shining One". Although little remembered, Mongolia suffered horribly at the hands of the communists (it was the first Soviet satellite state) and a cultural, spiritual, national and political revival is badly needed in that still suffering country which was once the center of the largest empire in history. We remember the man who should have been Bogd Khan and renew ourselves in the effort to see his successor recognized as such.

-MM

Readers interested in learning more about this remarkable man and his situation can look back at posts on How the Revolution Came to Mongolia and The IX Bogd Gegeen and Monarchism in Mongolia. It is unfortunate that a full restoration was not possible in his lifetime, though some progress was made with some political and military officials favoring at least some sort of official, ceremonial role for the "Holy Shining One". Although little remembered, Mongolia suffered horribly at the hands of the communists (it was the first Soviet satellite state) and a cultural, spiritual, national and political revival is badly needed in that still suffering country which was once the center of the largest empire in history. We remember the man who should have been Bogd Khan and renew ourselves in the effort to see his successor recognized as such.

-MM

|

| HH the Dalai Lama presiding at a prayer service on Saturday for the late Bogd Gegeen |

Sunday, February 19, 2012

Sunday, January 15, 2012

Sunday, January 8, 2012

Sunday, December 11, 2011

Thursday, September 15, 2011

The Mad Baron: Savior of Mongolia

It was 90 years ago today that a Bolshevik firing squad dispatched from this mortal coil Lt. General Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg and I had planned to post, for your viewing pleasure, an old Russian movie about the Baron (from the Soviet era so needless to say it was a rather negative portrayal) but, whoever put it on YouTube must not have had all their ducks in a row as it has since been removed. So, I shall instead address a pertinent topic concerning the impact of the mad monarchist of Mongolia on the current state of affairs in the far northeast. I don’t think I have mentioned it here before, but I have elsewhere, that I have a very low opinion of the fairly recent work by James Palmer titled, “The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became The Last Khan of Mongolia”. The title itself is rather misleading but, given how little coverage there is of the Baron, I had eagerly awaited the release of the book and was immensely disappointed with the result.